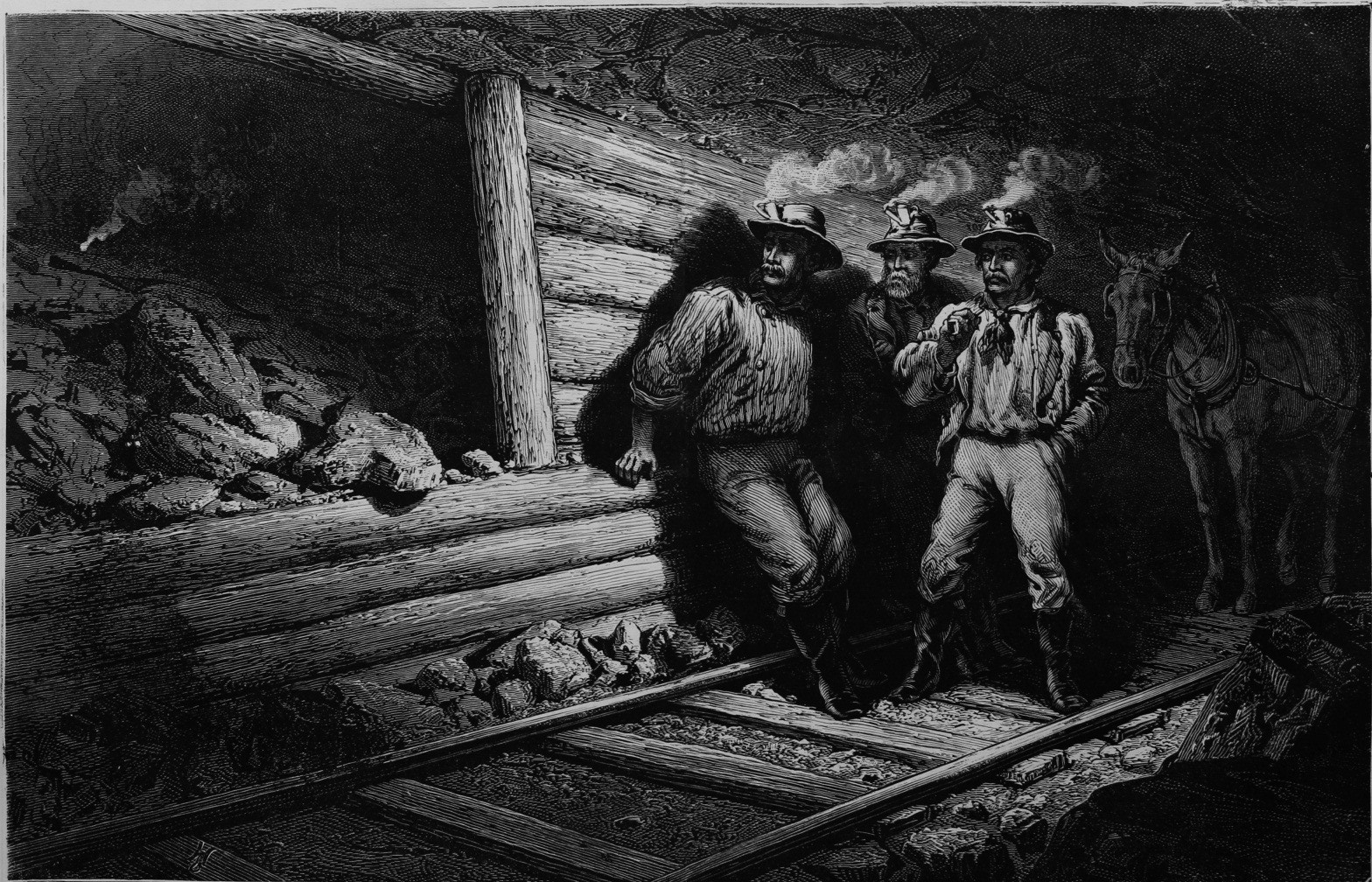

Coal miners in India, 2018

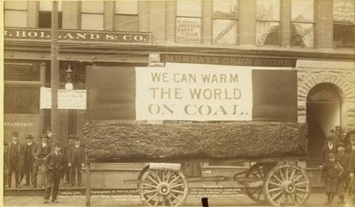

The strong link between coal and economic development is a well-worn theme in history, as the presence of mineral fuel facilitated industrial revolutions in Europe, great divergences between China and the West, and might have been responsible for representative democracy in the modern era. As we all know, though, coal is a dirty source of energy that provides great power, but at a high cost to the environment. Why can’t we just quit coal?

The New York Time’s recent piece asking this question cites the developing economies of China, Vietnam, and India as the main reason for coal’s grip on energy markets today. There’s no doubt in my mind that the existing infrastructure makes it easy to adopt mineral fuel and even tougher to quit it. The quick boost that coal offers to a developing economy is also a no-brainer; Americans made up the distance in 19th century industrialization in part because their mineral resources outpaced the European leader, Great Britain, over the course of just a few decades. For these reasons, it makes sense that coal still rules the energy regimes of the world’s most dynamic economies; its a long and familiar story to me.

What struck me most, though, about this recent piece is the obligatory firsthand description of the coal mine, which so often accompanies such articles. In 2018, the New York Times published this account of mining in India:

On a warm Tuesday in October, about a four-hour drive from Hyderabad, the capital of Telangana, an army of men in indigo shorts went underground to dig it out.

A simple pulley drew them in, a bit like a ski lift, except here, it took them deeper and deeper down a shaft. The creak of the pulley was all you could hear, and water, drip-dripping inside the earth. Here and there, off to the side, stood miners, their forms barely visible in the darkness, except for the belted flashlights that snaked across their bodies.

At about 900 feet below the surface, where the air was black and cool and the coal under our feet was squishy, a burst of explosives broke down a wall of coal. Small, sooty chunks were piled into tubs and wheeled out, then loaded onto coal trucks that hurtled down the country roads, sprinkling a layer of ash everywhere.

If you do any research in the history of energy, you’ll find yourself quite familiar with these kinds of descriptions. You get the sights and sounds of the underground environment, as if you were immersed in the mine. The author wants the reader to understand the otherworldly work of the miner, and the risks that such labors entail.

This is a very common theme in articles meant to introduce readers to the mines. One of my favorite documents in the history of American coal is Charles Barnard’s “From Hod to Mine in Seven Lifts,” which was published in American Homes magazine in 1874. Barnard attempted to explain to Americans the high cost in human suffering that came with the convenience of cheap and abundant mineral fuel. His description of a working anthracite mine in Pennsylvania:

It is not lovely work. There is nothing particularly attractive about it. Sometimes the roof falls in without warning, and death sits on the dusty coal heaps. It seems almost a surprise that any one can be induced to work here for any price. It is a long procession that ends with these miners. Coal heavers, sailors, railroad men, breaker boys, miners, – we are debtors to every one of them.

A dull explosion sounds near, and thick fumes of powder smoke fill the air. The sound of a drill under our feet gives a hint of the toil and danger all around. One of our party slips and falls in the inky water, and two of the big fellows spring to pick him up and ask if he is hurt. Their lips look red, and the whites of their eyes gleam brightly on their black faces. Their kindly words tell the true story. Men, men and brethren, all of them. Rough, grim with powder smoke, with hands hard with coal dust. What have we to do with them? Every thing. They toil in darkness and danger that we may have light and heat. It is to them we have come. Here the mountains may fall upon us. Here lie the glittering treasures we all so freely use without a thought of the toil spent in the winning. This is the price of a hod of coal.

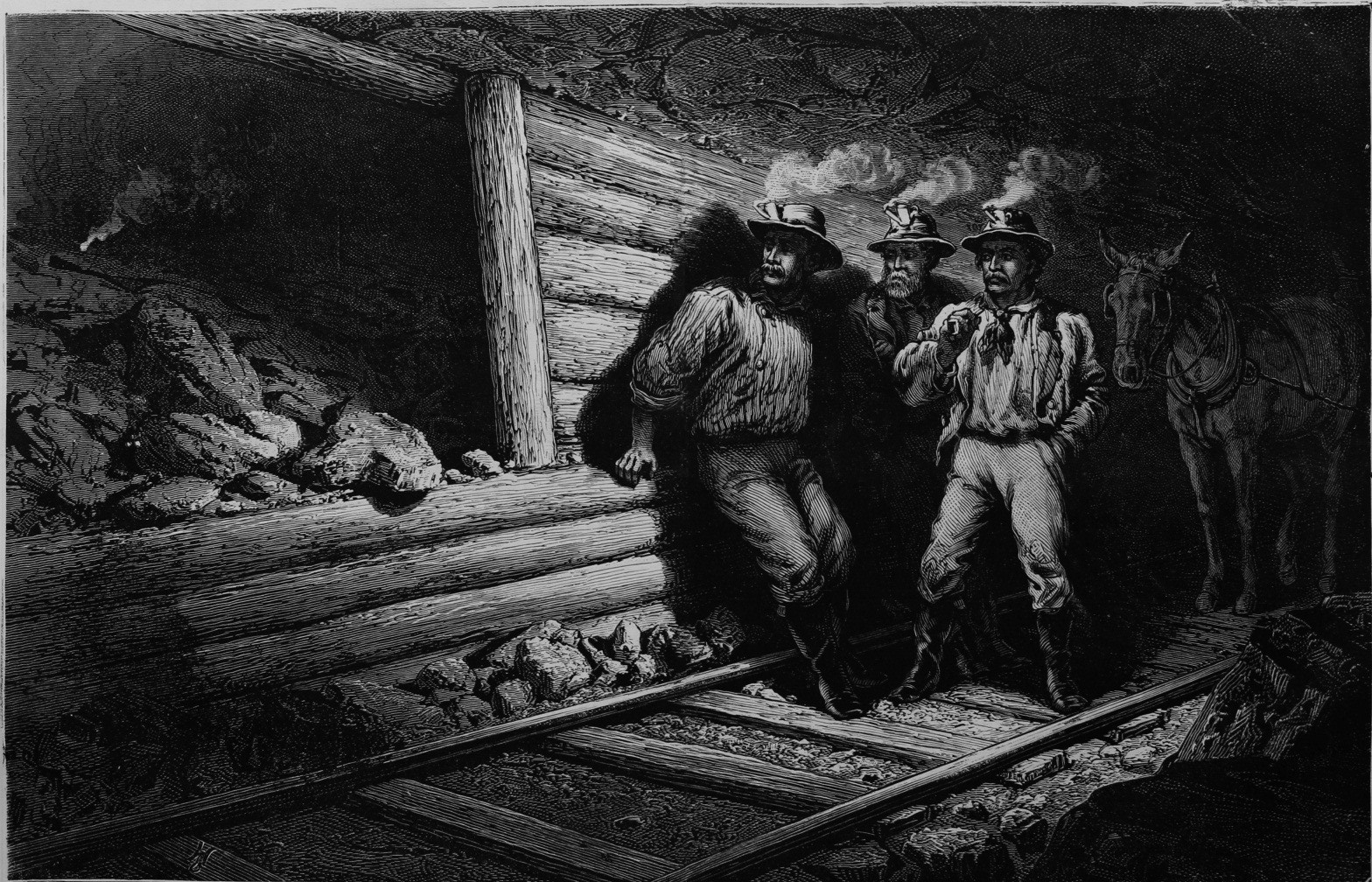

American coal miners, 1873

To go even further back, check out John Grammer’s description of mining coal in Virginia’s Richmond Basin more than a half-century earlier in 1818, in which enslaved African-American labored in the mines. Eastern Virginia’s mines, I should mention, were notoriously “gassy,” which meant that the risk of explosion or suffocation was a constant factor in the miner’s world :

Pickaxes are the only tools used in working the coal, as it breaks very readily, in the direction of the strata. The roofs of some of the passages are perfectly smooth; and in such, the light of the lamps, reflected from the great variety of colours in the coal, presents a very brilliant sight. The gloomy blackness, however, of most of the galleries, and the strange dress and appearance of the black miners, would furnish sufficient data to the conception of a poet, for a description of Pluto’s kingdom. A strong sulphurous acid ran down the walls of many of the galleries; and I observed one of the drains was filled with a yellowish gelatinous substance, which I ascertained, on a subsequent examination, was a yellow, or rather a reddish, oxide of iron, mechanically suspended in water.

What should we make of these tropes in popular pieces on coal mining? Perhaps there is the sense that extracting coal from the earth will never be “naturalized” as a human activity, even as modern standards of living are dependent upon it? What has become clear to me is that these brief visits to the miner’s world might produce some sympathy among readers, but if the historical trend holds, little work will be done to improve this otherworldly workplace for the health and safety of its residents. I applaud the work of journalists from every generation to enact change that will improve both our above ground and underground environments, but remain pessimistic about the outcomes.

I had the honor of contributing to the

I had the honor of contributing to the